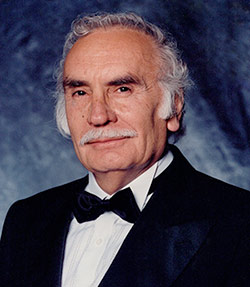

The Tony Maglica Story

By Jerry Reilly

Tony Maglica was born in New York City in November 1930, about a year into the Great Depression, and was baptized at the old Church of Saints Cyril and Methodius on West 50th Street in Manhattan. His parents, Jerko and Tomica Maglica (nee Jurcan), had emigrated from Croatia some years earlier. His father worked as a longshoreman when there was work to be found, while his mother kept the home.

As the Great Depression deepened and the family’s financial circumstances worsened, it was decided that Tony and his mother would return to her native village on the Croatian island of Zlarin, where living would be cheaper and they could live with her extended family. His father would remain in America, working when he could, sending money when he could, with the goal of eventually bringing the family back together in America.

In September 1932, when Tony was 22 months old, he and his mother departed New York by sea, bound for Croatia. Although neither Tony nor his mother could have known it then, Tony was not to set foot on American soil again for eighteen years.

Arriving on Zlarin, they were at first able, through frugality and hard work, to make an adequate, though not comfortable, subsistence. His mother worked a small plot of family land, producing a little food to eat. Tony, as soon as he got old enough, began earning extra money by repairing whatever broken things the neighbors would hire him to fix. But those relatively good times would not last. Europe was sliding toward war.

With the coming of the war, conditions went from difficult to dire. The money that Tony’s father had been sending stopped coming. The money he tried to send could no longer get through. All communication with America, in fact, was cut off. Work dried up. Food became scarce. Even local travel became impossible without the permission of the occupying authorities, and overseas travel was out of the question. The possibility of returning to America receded beyond reach. Tony and his mother were trapped in a war zone. They would, they realized, be in it for the duration.

As the war dragged on, conditions deteriorated even further, going from dire to desperate. The Islanders were subjected to oppression and intimidation, by the occupying forces: first the Italian and next the German.

In spite of the grinding poverty and pitiless oppression of the war years, Tony did manage to cultivate the interests and talents that, ultimately, would lead to his success as a manufacturer. He had always shown both interest and talent in a mechanical direction. At the age of 7 or 8 he took apart the family’s alarm clock, just because he wanted to see how it was made and how it worked. The adults were not pleased to find the alarm clock in pieces, so Tony put it back together – and, to the surprise of the grown-ups, it worked perfectly. But Tony was not destined to be a clockmaker. When the war ended and formal education became available again, he attended the trade school in Sibenik, where he was formally trained in mechanical arts and became an accomplished machinist.

The greatest of all his teachers, however, was his devoted mother. The values she imparted were values forged by hardship and misfortune: Courage, perseverance, determination, self-discipline, fortitude, self-reliance and a hope that was more than just hope. She endowed him with an optimism that no difficulty could dominate, no discouragement could smother, and no disappointment could crush. Even in the darkest hours she managed to keep her son assured that the bad times could not last much longer, that someday soon things had to get better. And she encouraged him with the idea that someday he would get back to America. There in America, she would tell him, you will find that nobody can stand in your way but yourself, and with hard work and honest dealing you can achieve whatever you can dream.

In the winter of 1950, at the age of 20, Tony did return to America. His hope was to find work quickly and earn enough money to send for his young wife and infant daughter. But Tony had a serious respiratory ailment. That was the only reason the communist authorities had allowed him to leave; but it would also turn out to be an obstacle to employment. He stayed with his father for a month to convalesce, but the situation did not improve. Tuberculosis was suspected. A cousin was able to arrange to get him into a hospital, where, as it turned out, he did not have tuberculosis but did have ailments including pneumonia and a collapsed lung. Tony remained under medical observation and treatment for six months.

While hospitalized, he began studying an English dictionary, mastering a few words each day. By the time he was cleared to work he could not yet speak enough English to find work as a machinist. Potential employers doubted that he would be able to read and follow instructions.

So Tony’s first job in New York was sewing clothes. It was a piecework job, with a base pay of 50 cents an hour; but with bonuses for working fast, he usually managed to make 70 to 75 cents an hour. By late 1952 he had saved enough money that, with some help from Catholic Charities, he was able to bring his wife and daughter to America. Soon afterward, his father was able to arrange for his mother to return. At last, the family was reunited in America.

Hearing that machine shop jobs were more plentiful in Colorado, Tony decided that Colorado was the place to be. With his wife and daughter, he traveled from New York to Denver by overnight train. Although he knew no one there and still spoke little English, he quickly found work as a machinist.

After about a year and a half in Denver, he heard that machinists could make three dollars an hour at the Douglas Aircraft plant in Long Beach, California. And so, in 1953, in a bald-tired Studebaker, the family struck out for Southern California. After more than one breakdown they arrived, only to learn that Douglas Aircraft would not hire him, even after he convinced them he was an American citizen, because they thought his English still was not good enough to read drawings. But Tony found work as a machinist at Pacific Valve in Long Beach. The pay was lower than he had hoped, so he soon moved to A.O. Smith, where he was able to work overtime.

Tony Maglica was not destined to be in the employ of some one else. From a co-worker at A.O. Smith, Tony learned that if he could buy a lathe and keep it at home, there were opportunities to earn extra money by making parts for his own customers on his own time. As soon as he had $125 saved up, he made a down payment on a Logan lathe and began doing contract work at his home in East Los Angeles in the daytime while working at A.O. Smith at night.

And thus began the meteoric rise of the Tony Maglica saga: First at making parts for pumps, then relocating to a farmhouse in San Gabriel, California, which had a garage, where he was able to work at any hour around the clock without complaints from neighbors.

Eventually Tony was forced to move from the San Gabriel property because a neighbor raised a zoning complaint about machine-shop work in a non-industrial neighborhood. Tony then made arrangements to share space in the shops of more established machinists.

By 1955 he had saved enough to rent a garage in South El Monte, California and move his machinery there. Now he had a machine shop that was his, alone and unshared, located in a proper, industrial-zoned building where nobody could say it didn’t belong.

He became a supplier of choice for critical aerospace and defense parts, and in fact made parts that went aboard the Vanguard satellite – America’s first response to Sputnik. In 1960 he applied for his first United States patent, for a turret lathe attachment that could hold multiple tools and quickly and precisely change them in and out. This was but the first of a great many inventions he would make and patent.

In 1979, Mag Instrument introduced a flashlight whose design Tony had been perfecting for years – the Mag-Lite® flashlight. Now an icon of American industrial design, the Mag-Lite® flashlight features a rugged machined-aluminum case anodized inside and out, immaculate fit and finish, a high-precision reflector carefully matched to the lamp, and a beam focusing feature that lets the user vary it from a wide flood to a tight, dazzlingly bright, long-reaching spot beam.

On December 11, 1978, Tony Maglica filed a patent application on the Mag-Lite® flashlight. That application became United States Patent No. 4,286,311 – the first of more than 100 United States patents he has obtained on portable lighting inventions. He is still an active inventor, with more patent applications pending today.

The Mag-Lite® flashlight quickly gained popularity among police officers and other first responders. The fact that people whose lives depended on their equipment chose the Mag-Lite® flashlight did not escape the notice of the general public. Neither did the fact that this flashlight came with something unheard of in the flashlight industry up to that time – a lifetime warranty. In a market where consumers had been accustomed to seeing a flashlight as a cheap, stamped-tin item of throwaway quality, this was a new and exciting experience: Now they could buy a flashlight with the expectation of owning and using it for the rest of their lives.

The success of the Mag-Lite® flashlight was followed, in 1982, by the introduction of the Mag Charger® flashlight – Mag Instrument’s first rechargeable flashlight. With a beam distance of well over 400 meters, it cemented Mag Instrument’s reputation with the law enforcement community and raised the company’s prestige with the general public.

The product that truly made Maglite a household name and a consumer-market favorite, however, was the Mini Maglite® flashlight. With beautiful lines that have earned it a place in many museums including the Museum of Modern Art (among many other industrial design honors), the Mini Maglite® flashlight featured the same flawless fit and finish, the same anodized machined aluminum construction, and the same spot-to-flood focusing as Mag Instrument’s larger flashlights. Introduced in 1984, the Mini Maglite® flashlight grew rapidly in popularity. By 1985, it was being touted in newspapers as “the hottest-selling gift item of the holiday season.”

Acclaim continued to mount. Often referred to as "A Work of Art That Works®," the Maglite® and Mini Maglite® flashlights were honored by the Japan Institute of Design and by the Museum for Applied Art in Germany. Fortune and Money magazines ranked Mag Instrument® products among the top 100 products that "America makes best." Mobile PC Magazine called it “one of the 100 greatest gadgets of all time.”

In 1996, the Wall Street Journal referred to the Maglite® flashlight as "the Cadillac of flashlights," and quoted then-CEO of Apple Computer Gilbert F. Amelio as saying he wanted Apple to be "essentially the Maglite® of computers." In that same year, by which Mag Instrument’s payroll had grown to over 1,000 persons and annual sales were in the quarter-billion-dollar range, Ernst & Young named Tony Maglica it’s “Inland Empire Entrepreneur of the Year.”

Other successful new product introductions have continued apace. These have included a smaller AAA-Cell version of the Mini Maglite® flashlight, ideal for many industrial and medical applications; the Solitaire® single AAA-Cell flashlight, small enough to fit on key chains and in purses; and LED flashlights including the new ML and XL series of machined aluminum, focusing-beam flashlights and the Mag-Tac® flashlight, Mag Instrument’s latest tactical flashlight and its first powered by Lithium CR123 batteries.

Tony Maglica is still in day-to-day charge of Mag Instrument. He continues to work 10-12 hours a day and six days a week, and to develop and launch new products. And he remains a prolific inventor.

Mag Instrument’s flashlights are now exported to more than 100 countries around the world. New products are constantly under development at Mag Instrument, but they are introduced only when Tony Maglica is personally satisfied that their design and operation are up to Mag Instrument standards.

During and after the Balkans War of the early ‘90s, Tony Maglica felt compelled to help the region where he grew up. He contributed extensively to fund relief efforts including medical care for war-wounded children. After hearing about a child who had been horribly burned in an accident with a kerosene lantern, he arranged through Catholic Charities to donate 50,000 flashlights for use by families that were displaced or were otherwise without electricity in their homes. At the behest of an order of nuns, he donated all the furnishings for Dje?ji Dom Sr. Terezije Od Malog Isusa, the home they were establishing in Zagreb for war-orphaned children. In 1997 he instituted the Maglite Foundation, whose mission is to foster economic development in Croatia.

Tony Maglica also has made it a practice to donate flashlights for use in public emergencies and civic events. Forty thousand Mini Maglite® flashlights, each marked “Remember Sarajevo,” were featured at the closing ceremony of the 1994 Winter Olympics at Lillehammer, Norway. Tens of thousands of Mini Maglite® flashlights were also used in the “Thousand Points of Light” ceremonies during the inaugurations of President George H. W. Bush, and later, of President George W. Bush. In the wake of the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center in New York, Mag sent flashlights for use in the rescue and recovery effort at Ground Zero. Similar donations were made in the aftermaths of the Oklahoma City bombing and Hurricane Katrina. Flashlights were also donated to U.S. troops in Operation Desert Storm, and to relief workers in the wake of the Japan Tsunami of 2011.

Under Tony Maglica’s direction, Mag Instrument also donates to numerous charitable causes such as cancer research, children’s diabetes research, Doctors Without Borders, AmeriCares, and the Fallen Police Officers Memorial Fund.

From Tony Maglica’s childhood home to the birthplace of his success, this patriot and businessman continues to champion and exemplify the blessings of free enterprise.

Index

- WHAT CAN CROATIA DO FOR YOU

- 20 Years of CroatiaFest

- Trg Kralja Tomislava, Zagreb, Croatia

- FAMOUS CROATIAN STATUES

- HRVATSKI JEZIK , CROATIAN LANGUAGE Who Are The People In Your Family

- KRALUS

- CROATIAN TRADITIONS By Cathryn (Mirkovich) Morovich

- AMERICAN CROATIAN CLUB OF ANACORTES CELEBRATING 45TH ANNIVERSARY

- The Early Croatians of Old Tacoma in Pierce County

- Traditions

- Passed On Croatian Traditions

- Coffee-Break Treats From The Old Days

- Augie's Tavern, Cle Elum

- The "Bakalar" Notebook

- Remembering Basement Food

- Lowman Lunch

- Did You Know?

- Hrustule - a Croatian Christmas tradition

- The Tony Maglica Story

- Famous Pioneer of Silicon Valley: Victor Grinich

- UNESCO

Have a good story? Why not share it?

Send your story to info@croatiafest.org.